Yazar: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Assel Tutumlu – 27.10.2020 Now with the sequel (Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan) released on Amazon Prime on October 23, Borat 2 is aiming to mock the US bigotry once again by using the image of Kazakhstan. Although thousands have signed the petition to cancel the movie, it went through, thereby renewing the conversations about the fine line between political humor and discrimination. As people of Kazakhstan living abroad are trying to fight off the stereotypes, the movie is not longer a comedy for them. Scholars such as Erving Goffman defined this position as stigma “referring to an attribute that is deeply discrediting” causing a spoiled identity. Spoiled identity appears when “unwelcome discrepancy between virtual and actual social identity vis-à-vis ‘normals’ for whom no such discrepancy occurs.” It creates a label in a binary manner with some people being abnormal, while others are normal. It attacks the dignity of the group and prevents them from operating as a full member of society. Moreover, stigmatization attacks a person in private, which undermines their capacity to fight off the derogatory or discriminatory comments. Although literature calls for political activism, and such policies may exist in social media, the daily experience of individuals and groups targeted by harassing jokes from strangers and people they meet on a daily basis suggests that stigma remains for years to come.

When the movie Borat (Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan) first appeared in 2006, I was in the United States working on my PhD dissertation. For the next six(!) years I, as well as countless of my country-men and women, kept hearing the same question: ‘I know that the movie is fake, but is it true that in Kazakhstan….”. My usual reply was: “the movie used the official symbols of the Government of Kazakhstan; the rest was fiction.” The village of Borat was filmed in Romania, the characters spoke Armenian, the anthem, scenes and everything else was made up to frame the unaware Americans in the movie in awkward situations and mock their reactions. Although people understood that there was an irony in the movie that aimed to ridicule ignorance and prejudice in the US rather than expose Kazakhstani culture, people still hoped to find at least something true about my country, be it a position of women in society, foreign relations with neighboring Uzbekistan or the level of poverty and education. The situation was even worse for Kazakhstani kids who were bullied and harassed in American schools.

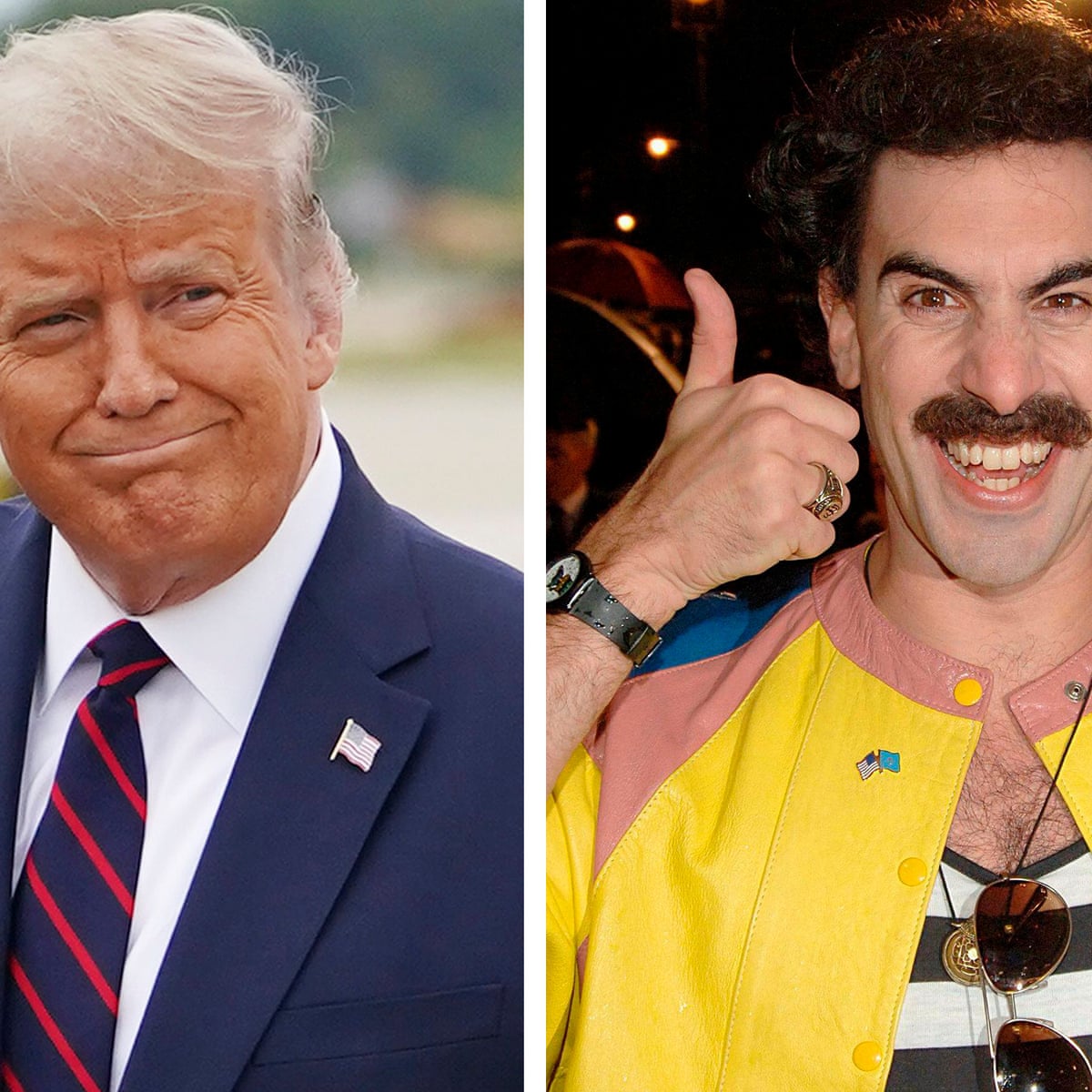

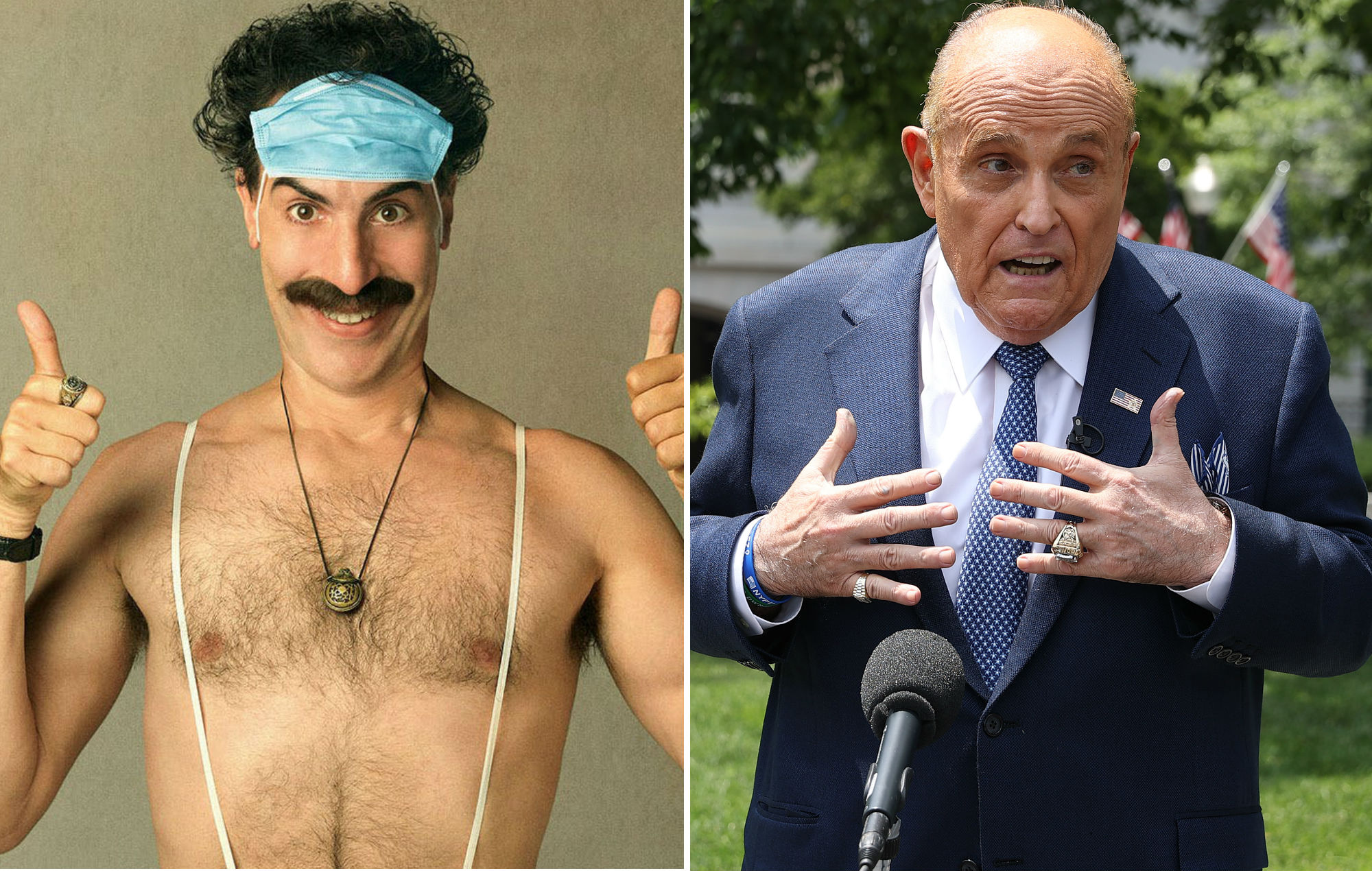

Indeed, scenes in Borat 2 do show the worst of the United States. The plot of the movie takes the main character, played by Sasha Baron Cohen, and his ‘daughter’ Tutar, played by Maria Bakalova, to the United States in order to ‘gift’ the daughter to Trump and extort favors for Kazakhstan. By doing so, Borat meets high-end politicians, including Rudy Giuliani, President Trump’s lawyer and a former mayor of New York in a hotel room. In the scene, Borat offers him his ‘daughter’ to pay respect to the President Trump and when he leaves, Tutar and him go into a bedroom with camera capturing Bakalova “reaching into Giuliani’s shirt to retrieve his microphone as he gives her a pat on the back”. Giuliani then lays down on a bed with both hands inside his pants, when Baron Cohen bursts into the room telling Guiliani that "She's 15, she's too old for you." Although Giuliani sent a statement that he was only ‘tucking his shirt’, many easily believe in possibility of such misconduct happening in the highest echelons of power in the US. Borat also tackled Mark Pence, the Vice President of the United States, by offering him his daughter at an event wearing Trump’s mask. Politicians were not the only ones who were targeted. By donating to the “March for Our Rights” group that supports gun ownership and stands for the “resistance to the U.S. federal government's involvement in local affairs”, Sasha Baron Cohen was able to troll the right-wing militia by singing an 8-minute song with lyrics that called for the mask-wearers to be injected with the "Wuhan flu” or be chopped “like the Saudis do”. His audience sang along. The song also mocked CNN, Barak Obama, and the World Health Organization. Such political mockumentary attracts admirers of Cohen’s talent to frame politicians and various groups in a way that exposes their atrocious behavior in natural settings leaving very little room for legal action from these actors.

However, this story leaves the other side of the coin unexplored. The whole movie also negatively defines the Kazakhstani people without giving them an opportunity to define themselves. By using a country of 18 million people that was unknown to a general American audience, Cohen created a set of stereotypes about Kazakhstani people by pre-defining the country way before it could introduce itself. As a result, people of Kazakhstan acquired a stigma that was hard to fight off. The Kazakh government tried to fight off the stereotypes after the first movie. Former Minister of Foreign Affairs, H.E. Erlan Idrissov wrote in The Times that “We survived Stalin and we can certainly overcome Borat's slurs”. In addition, Kazakh government also worked on changing popular perceptions by preparing hand-outs with the “Common Misconceptions in the West about Kazakhstan”. Although Borat had put Kazakhstan on the mental map of Americans, Kazakhstani government realized that they were in a desperate need of the nation-branding. The Government then spent USD10 million for creating the country’s image abroad. In addition, Kazakhstan donated USD40 million in making their own movie “Nomad” to challenge Borat, but the epic only collected around USD 80,000 in the box office revenues in the United States. These official activities prompted people to say that Kazakhstan did not understand the point of the joke, hence turning defensive. It should have embraced it, the argument went. However, such care-free attitude is hard to come by at the time when people have preconceived notions about one’s identity and a country where they are from.

Borat 2: Between Mockumentary and Stigmatization