Yazar: Busenur Yıldırım – 17.05.2021 Myanmar has alternated between military and civilian leadership since 1948, but the Tatmadaw has always had notable power. The United States and other European countries imposed sanctions on the country to force its rulers to implement pro-democracy reforms for years, and in 2011 the military finally conceded some power to civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD to rule the country. Aung San Suu Kyi received support from all over the world and advocated democracy, despite being held under house arrest for nearly twenty years, and her efforts earned her the Nobel Peace Prize. After taking office, San Suu Kyi treaded carefully around the strongmen of the Tatmadaw, as she refused to challenge the military on the 2017 genocide campaign against the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic minority group in the country. But in 2020, she campaigned to restrict the military's role in running the country, and in the parliamentary elections held in November,her party won a victory on that platform. But the generals, who saw this as a direct threat to their power, claimed that the election was fraudulent and struck the democratic government from power with a coup. The 8888 Uprising and International Reactions Prior to the coup, Western engagement with the country was minimal and rather cautious, owing to sanctions from the US and the European Union, imposed in the 1990s to punish the Myanmar administration for stealing elections and imprisoning dissidents. Evidently however, twenty years of sanctions and superflous engagement achieved very little. Among others, an important factor which makes Myanmar a difficult case for the west is the relative support the country’s elite enjoys from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). In a similar vein, China, one of the largest investors in Myanmar, too has amicable relations with both the military and civilian elite. Cautious in not alienating Aung San Suu Kyi or the military hierarchy that detained her, Beijing responded to recent events by saying that ''China is a friendly neighbor of Myanmar’s. We hope that all sides in Myanmar can appropriately handle their differences under the constitution and legal framework and safeguard political and social stability”. The situation is complicated however by Tatmadaw’s distrust of China and its courting of democratic countries. In this regard, neither China nor the US want to give the other an advantage in Myanmar. So there is currently not much that ASEAN or any other country can do to affect events in Myanmar. China is not trusted, and the Biden administration’s rhetoric on human rights and democracy is too risky for the generals to invest in. ASEAN too would be hesitant to take such an approach because two of its members have communist systems, and a third of Thailand has recently suffered a coup. But in the long term, this is unlikely to solve Myanmar's problems. The country is already facing a severe economic downturn due to COVID-19, widespread poverty, and conflicts involving dozens of armed groups. Essential services, including banking, healthcare, and government functions, are on the brink of collapse and with the ongoing fighting between local militia groups and the junta, major foreign investors like China are likely to avoid the country. Singapore, another important foreign investor in Myanmar, has already expressed "grave concern" and described the use of lethal force against protesters as "inexcusable". So for the long haul, a much stronger pressure but also engagement from the West may be needed to keep the country stable. All in all, while ASEAN’s engagement alone will not move the generals much, a coordinated pressure from the West may, in the long term, yield some results.

On 1 February, Myanmar’s decade-long experience in constitutional democracy and civilian rule came to an abrupt end when the Tatmadaw - as Myanmar's military is called – seized power from the elected ruler of Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the National Democratic Union Party (NLD). Besides Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint and other officials from the National Democratic League were detained and the military said they would remain in control for at least a year with supreme authority resting with Min Aung Hlaing. Army officials further claimed that the detentions were carried out in response to alleged election fraud as 24 ministers and deputies were dismissed, and replaced with 11 high-ranked soldiers. When widespread protests were held across the country and the staff at hospitals and other medical facilities across Myanmar stopped working to protest the coup, the new “government” responded strongly by arresting dozens and imposing a blockage on Facebook, Messenger, and WhatsApp services, in favor of protecting the ‘'stability''.

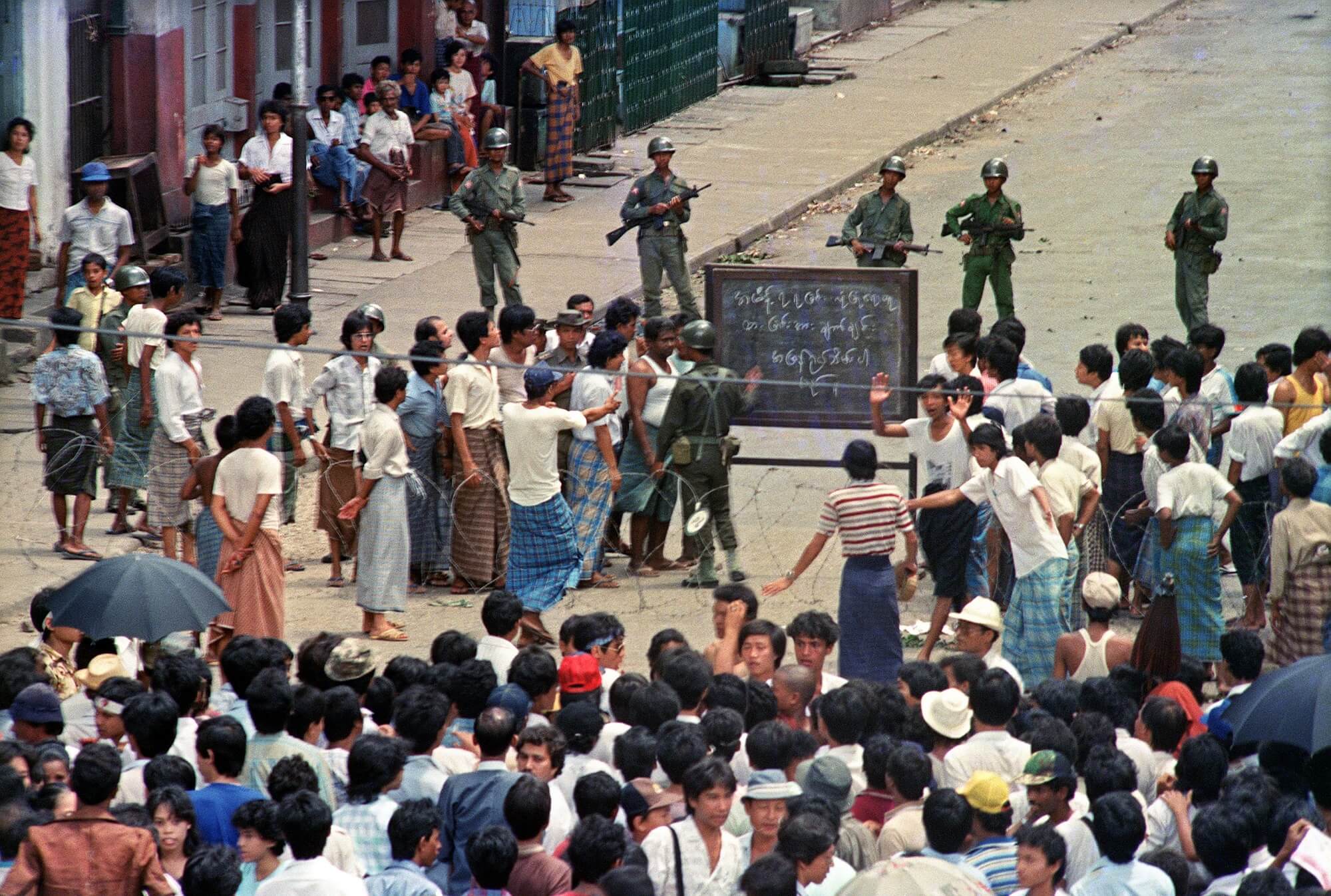

The Tatmadaw endured occasional riots, demonstrations, and various coups but the 1988 uprising was a watershed moment. By 1988, Myanmar (named Burma back then) was ruled for 26 years by General Ne Win who seized power in a coup in 1962. General Ne Win severed the country from the outside world, refusing to take sides in the Cold War. Instead, he implemented a one-party system under the Burmese Socialist Program Party, which was dominated by the military. This led Burma to become one of the poorest countries in the world, and together with local corruption and police brutality, triggered a set of riots, led by students in Rangoon (now known as Yangon), the country's then-capital and commercial hub. Students, together with civilians, disgruntled soldiers, and Myanmar's Buddhist clergy, began daily marches to call for democracy and respect for human rights. General Ne Win resigned in July but another General, Sein Lwin took over as his successor. On August 8, 1988, a general strike was called and demonstrations were held simultaneously all over the country. The protests which were crushed by the military, leaving thousands dead, acquired international fame as the 8888 Uprising.

The recent coup was condemned straight away by the West. The White House issued a statement urging that the military and all other parties to adhere to democratic norms and the rule of law and release those have detained which added that the “United States will take action against those responsible if these steps are not reversed.” The European Union also joined the Biden administration to draw attention to the importance of human rights and announced a set of sanctions in coordination with the US. The United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said the coup "constituted a serious blow to the democratic reforms in Myanmar". And the British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in a Twitter post that “The democratic wishes of the people of Myanmar must be respected, and the National Assembly peacefully re-convene”.

But ASEAN could nonetheless keep things from getting worse. As long as ASEAN appears to be engaging with the junta, other countries may allow ASEAN to lead on their behalf, stopping the generals from taking reckless actions in the short term. The so-called five-point consensus issued by the bloc on steps to end the violence and promote dialogue between the rival Myanmar sides which includes ending violence, a constructive dialogue among all parties, a special Asean envoy to facilitate the dialogue, acceptance of aid and a visit by the envoy to Myanmar is also a good starting point.

What is happening in Myanmar?